Injecting Files into an Archive Format I Don’t Understand

Somewhat recently I was a part of the group reverse engineering files for smash ultimate, and one of the problems we encountered is that we were figuring out just about every file type faster than the 14 gigabyte archive they were contained. This creates an interesting scenario of a lot of code being written, but little to no testing done. Feeling antsy about wanting to try some modifications on hardware, I decided to try to figure out a temporary solution to help us get by.

Extracting Files

Talking about injecting files into an archive is getting a bit ahead of ourselves if we don’t even know what the files we’re replacing look like. So how do you extract files from an archive format you don’t understand? Well, in this case the giveaway is compression.

In this case, our archive uses zstandard compression, a compression algorithm developed by facebook, for a majority of its files. One question I get quite frequently is “How do you figure out compressed data?” Here’s what my process tends to look like:

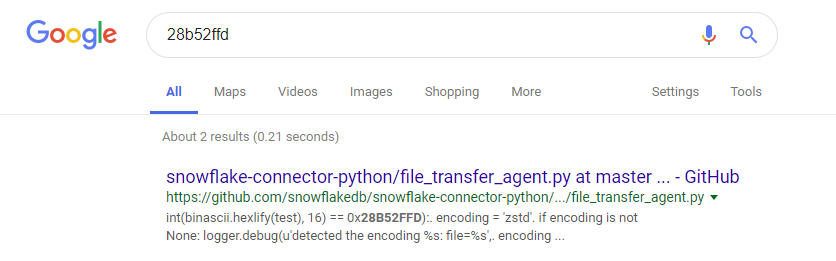

- Look for “magic”, or data at the beginning (or, on rare occasions, the end) that is constant and used to indicate what a block of data is, this is pretty common practice both for files and compression types. In the case of zstandard, we have a magic of “28 B5 2F FD”, which when googled yeilds:

which pretty much tells us all we need to know (encoding = ‘zstd’). With enough exposure, recognizable magics like zlib’s will be possible to pick out without even thinking about it.

- Look at the environment. Do you have a copy of the binary that would be parsing these? Check for imports to see if it’s using a system or dynamic library provided decompression algorithm, sometimes it’ll be as simple as finding “lz4.dll” sitting beside the executable. Have no information other than what type of machine it runs on? Look for developer documentation on the system to see what types of compression have implementations provided to the system. Worst comes to worst, find the code for parsing the file by other means and figure it out using static analysis and pray it’s not custom.

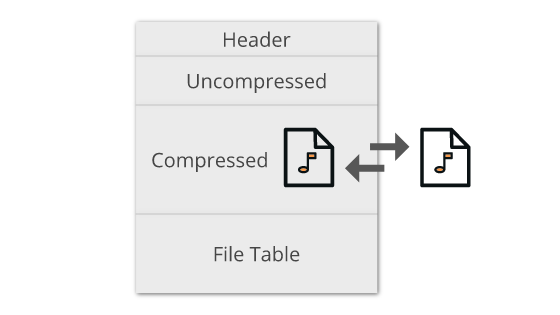

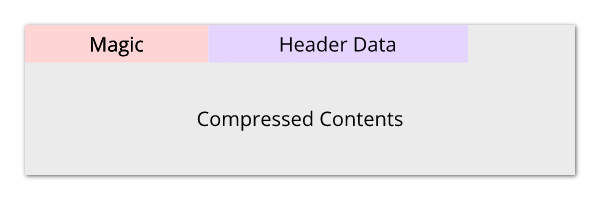

Simplified view of a zstandard compressed block

Simplified view of a zstandard compressed block

Now we know how to find all the compressed files with somewhat reasonable accuracy: search for the magic, parse the header data of zstd to find the compressed size, then copy it out to a file. Or… if you’re lazy like me just see that the files are back to back for the most part (see image below) and choose to just split the files by the magic and hope not too many files break.

Search results for zstd magic

Search results for zstd magic

Injecting Files

Now we have some (tens of thousands of) filename-less files and we use tools like grep to find the one we want to modify (Note: it’s worth mentioning that using file magic to separate files by type makes this a lot easier to work with). From here we figure out the file format, modify some data and now we want to put it back in. Some assumptions we can make:

-

Somewhere in the archive the size of the file compressed (and likely uncompressed as well) is stored.

-

There is may be a sanity check by hashing the file and comparing to a hash stored in the archive (not common, but often used in things like save formats as they are written multiple times and this ensures they aren’t loading an unintentionally corrupt save)

-

(Only because I learned this in the process of extracting) Zstandard stores info in the compressed data’s header about the size of the compressed file. For many zstd implementations, including extra bytes on the end may raise an exception, ending our fun and in this case closing the game.

Knowing this, we gain our constraints:

-

The compressed and uncompressed file sizes must remain the same

-

(Self enforced) our data must functionally remain the same.

To figure this out we’ll have to look at the fundamental idea of compression. Let’s take a look at how two pieces of data would be compressed by a hypothetical compression method

Data 1

------

00 00 00 00 -> 00 repeated 04 times

Data 2

------

01 02 03 04 -> 01 repeated 01 time, 02 repeated 01 time, 03 repeated 01 time, 04 repeated 01 time

So we take the same number of bytes, use the same compression method on them and, while the data with a lot of repeating bytes compresses by 50%, the data with no repetition doubles in size. While every type of compression is different in one way or another, for the most part repetition = better compression.

Injecting Level Data

Now let’s look at how I did my first level data injection, shown in this tweet:

First smash ultimate compressed archive mod and first stage mod afaik https://t.co/k1lx8QAkVM

— jam1garner (@jam1garner) November 25, 2018

Thanks to @Raytwo_ssb for testing and recording, luckily it only took one try 😎

The mod itself is changing three floats (decimal values) in the file. One float of the y coordinate of a point in the collision, one float of the lower y bound of the camera box, and one float of the lower y bound of the death boundary.

Visualization of the tested mod

Visualization of the tested mod

Now we need to somehow make the file compress to the exact same size as before without changing anything functionally. To do so I choose to modify the float values. Let’s take a look at two float values to see why this works:

1.00 - 00 00 80 3F

1.01 - AE 47 81 3F

So, generally speaking, more precision in our floats means it’s more random, and therefore less compressible. With that information, we’ll be able to make small adjustments to floats in order to nudge the compressed size up and down. The other adjustment we control is what level of compression we use. Typically, in compression, the level of compression is a trade off between time to compress/decompress and the compressed size of the file. So if we increase the compression level, the file will become more and more compressed, allowing for our minor edits to have more of an effect. With this we can tweak compression level until it’s as close to our original size as we can get, and then make floats more or less precise to slightly tweak our file size until it matches the original.

Injecting a texture (Hard mode)

Injecting a texture, which I eventually did, (see tweet below) turned out to be much more of a challenge.

Here's the first (afaik) texture edit in smash ultimate, texture edit by @KillzXGaming, injected into the game by me pic.twitter.com/58t0o59dhb

— jam1garner (@jam1garner) November 29, 2018

With textures, there’s not only a lot more data that isn’t free for us to tweak, but due to a lot of repeated use of the same color (and therefore the same bytes), it compresses a lot more. And since we have to modify a lot more than 12 bytes to make a meaningful texture edit, it means we won’t be starting from a point that is close to the original compressed file size. Even after adjusting the compression level, the closest I could get was still over a KB away, and at compression level 1 (the worst case scenario for this technique) no less! This meant I would have to find a large area to have control of without messing up how the texture looks. In the end I ended up settling on the smallest “mip map” or texture level of detail.

Mip maps visualized

Mip maps visualized

So mip maps are more or less just prerendered downscaled versions of a texture included within the texture file for when the object is low res enough of the screen that the full resolution of the texture isn’t needed. Since the lowest level mip will only be used with the texture is a couple pixels on the screen, modifying this won’t affect the user experience. So in this case, I just replace the mipmap’s texture data with any data I want, and adjust that data until the file size matches using a similar technique to before.

Conclusion

While this certainly isn’t the best solution to the problem of wanting to replace files, mainly due to its context-specific requirements being hard to generalize (what if a file needs to be byte perfect? won’t work), it has its benefits as a quick and dirty solution that doesn’t really require understanding the archive. (Not to mention being a fun challenge).

Questions/Comments/More? My twitter: https://www.twitter.com/jam1garner