Reverse Engineering MSC Bytecode — Fuzzing for a Crash

Often times one of the hardest parts about reverse engineering an executable is finding the code relevant to your needs. Behind even the most simple consumer applications is tens of thousands of (likely unlabeled) instructions, and since the logic relevant to you likely runs for an unimaginably small amount of time you won’t just be able to freeze the program on that issue to see where it is. On top of this, with embedded devices there are often plenty of limitations to your ability to debug, so attempting to stop with the correct timing may not even be an option (not that it would be a great option anyway).

One option on how to find relevant code is to look for strings such as filenames, error messages, or default values. The problem is, if you’re working with part of an embedded system that has very limited direct I/O you probably aren’t lucky enough to have relevant strings, so you have to resort to figuring out something unique for your situation on how to figure it out. In the case of MSC the way we decided to go about finding it is by trying to find a crash, and to use the rudimentary crash handler available to us in order to trace said crash back to the code we want.

At this point, while we didn’t know the full extent of what a majority of the commands in the MSC interpreter do, we’ve at least been able to figure out the size of each command, which is enough for us to “safetly” modify a script in an attempt to get a crash. It’s important that the script data being executed is what causes the crash, as if it crashes on load we might have to figure out the resource loading/access system which is a bit more effort than we probably want. So we have two ways we can typically go about doing this in order to fuzz for crashes:

-

Set up some sort of automated fuzzing system — due to the fact Wii U homebrew was (and still is to an extent) limited, this option isn’t really viable, it would require quite more effort to setup than is worth the payoff as well as being overkill.

-

Think out how I myself would write each command and think about what data I can give each command (without breaking the parser) that will likely cause your typical C++ crashes (out of bounds access, divide by 0, etc.)

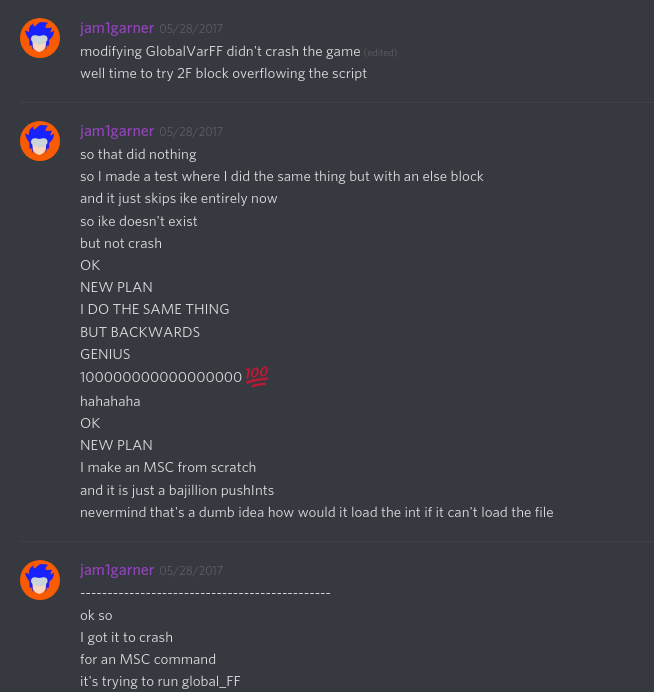

Here’s how my (very sleep deprived) self monologued about the process during my last couple hours of fuzzing the interpreter:

Things like trying negative values, out of bounds values, or an excess of values are all good plans on how to attack these sort of systems. Funny enough one of my last couple solutions (as seen in the screenshot above) was “just a bajillion pushInts” which, funny enough, would’ve also worked despite the fact I dismissed it as a “dumb idea”, so lesson learned there’s no dumb ideas! I’ll explore why in a future blog post going over all the vulnerabilities I found in the interpreter.

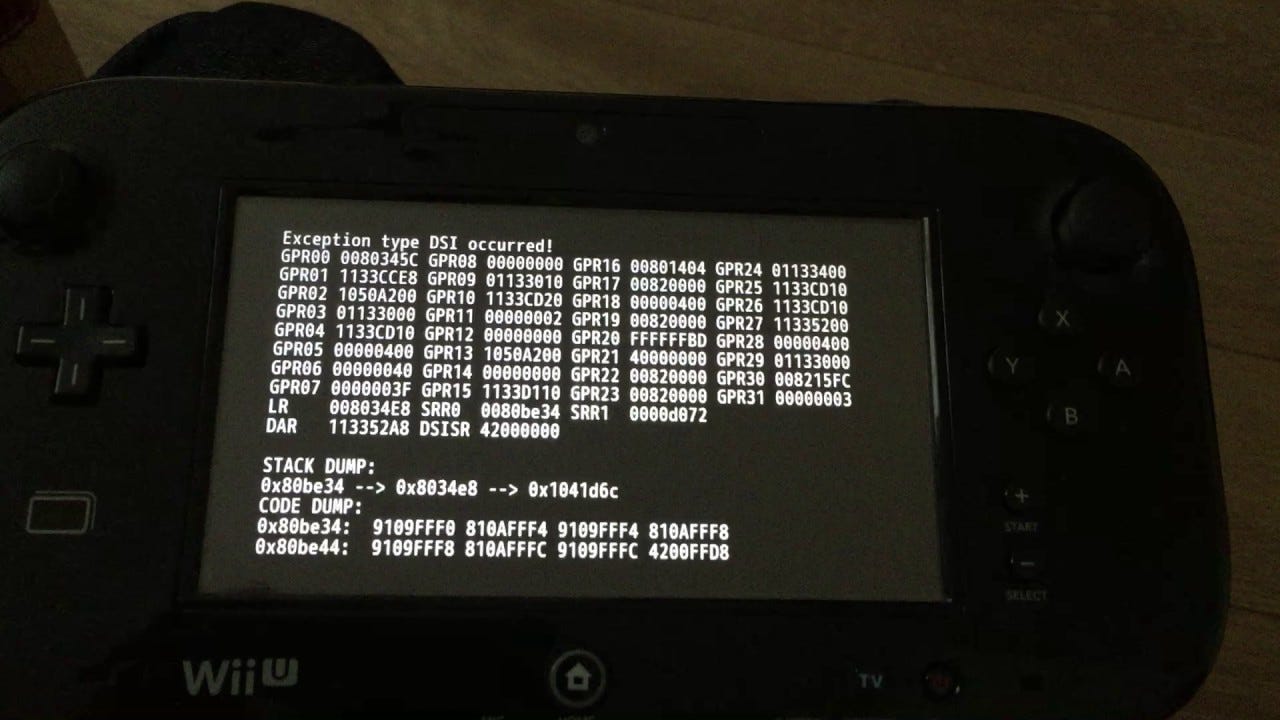

Now that we’ve gotten a crash we can take a look at the what caused it(either through a debugger or just from a crash dump). In this case calling what we originally called “global_FF()”, which is the highest numbered syscall. The syscall system used in MSC is pretty much just a simple means of calling select native functions from within MSC. If we inspect the address of the code it crashes at, we find out the crash was actually just it jumping into the .bss, which is mapped as readable and writable but not executable.

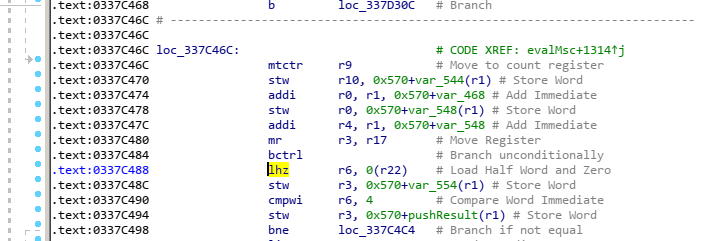

So instead we can look at the link register, which stores the return value when a function is called, which is actually mapped to code we get:

bctrl or “Branch to CTR register and Link” is essentially calling a function at the address in the CTR register, which makes sense for the syscalls as it takes an index, gets a function offset for the index and then calls it, which would require either a really large switch statement or something like this where it calls a function from a vtable. The only check that is done when calling this is ensuring the function pointer is not NULL, meaning that if we call a function far enough outside of the vtable that it overlaps non-zero data we will attempt to call a function in memory mapped as not-executable resulting in a crash.

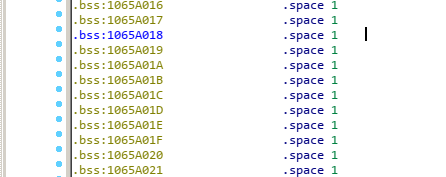

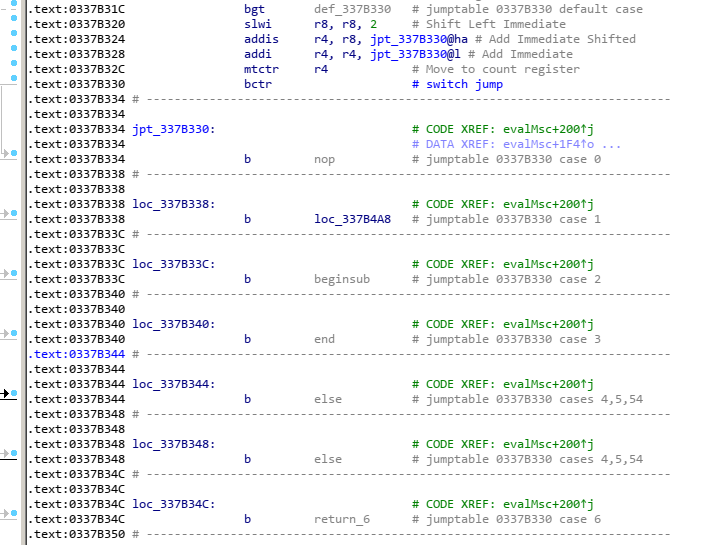

Now that we understand the crash we can work our way backwards through this logic and we’ll find a large jump table which will look something like this: (IDA recognizes it as a jump table for us, but at the time it was unlabelled)

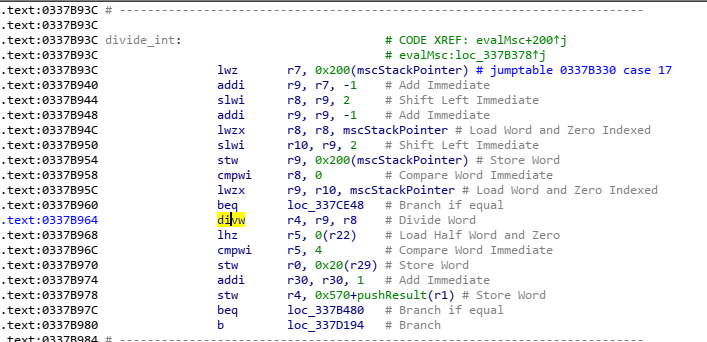

It’s pretty easy to guess that this table is a big switch statement being used to handle each command, this can easily be verified by looking at simple commands like divide which we already labelled. Divide is command 0x11, so if we find the case for 17 and look through it we’ll find a divw (divide word) instruction, which is enough to reasonably be assured this is indeed the divide command as we suspected.

For reassurance though, going through add/subtract/multiply and seeing them all be the same aside from one or two instructions help as well. However if you’re well versed in PowerPC assembly you might’ve noticed that before dividing r9 by r8 it checks if r8 == 0, and if it is jumps to some different code. This is because the interpreter needs to handle divide by zero issues in a way other than crashing the entire console, and is further proof this is in fact our divide command.

Next blog post I’ll cover the process in which I reversed how the interpreter works and go over some of the more interesting commands to reverse. If you’re interested in that you can follow me here on medium or on twitter to stay updated.