Extracting Files From an Archive Format I Understand Way Too Much

Ok so long-time followers of mine might catch it, but the title is in reference to a 2018 blog post of mine: "Injecting Files Into an Archive Format I Don’t Understand". It's one of the posts I'm more proud of, so I'd definitely recommend checking it out, especially if you're interested in file format reverse engineering, or just an "explain it like I'm 5" of the reverse engineering mindset. However, it has been quite a long time since 2018, so I think it's time for an update.

TLDR on the last post in the series: Smash Ultimate has a single massive archive containing its assets called "data.arc", I figured out how to inject mods into the game without really understanding the format with some corner-cutting trickery.

Quick Smash Modding Catchup

So a lot of relevant stuff has changed since my last blog post in the world of Smash Ultimate modding since my last blog post in this series.

Quick rundown:

- The game released. Since uh. It hadn't been by the time I was the first to get mods running in-game, as seen in the last post.

- The game has received 9 major updates, the first of which massively overhauled the archive format. (As well as 6 minor versions and quite a few patch versions)

- Multiple arc-related tools have been released:

- Multiple means of modding files have been released at various points:

- After my blog post, I made a simple python script for injecting files automatically

- SSBU Mod Installer - My script was ported to PyNX (A python interpreter homebrew for the Switch)

- ArcInstaller - An ArcCross-based solution for mod injection

- I wrote saltynx-arc-mod-installer, a mod which installed your mods when you booted the game. (Note: I have no memory of writing this or it existing but I'm told it was popular? At least for a short period of time)

- Ultimate Mod Manager (UMM) - A homebrew application based on saltynx-arc-mod-installer that was basically all around better

- ARCropolis - A Skyline mod written in Rust designed for adding native mod loading support to Smash Ultimate, created by Raytwo from a proof of concept of mine.

Most notable of them is Arcropolis which, unlike the rest of the mod loading techniques, functions by modifying the resource loading system directly as opposed to modifying the archive on disk.

How the Archive Format Actually Works

There has been a lot of benefit to having so many eyes on the arc works, it's a complicated format and I certainly wouldn't have bothered to put in the hours it'd take to reverse all this by myself. All of this has been a collaborative work from the start—people like Ploaj, Shadow, and ShinyQuagsire also played a large role at various points in this endeavor. Credit where credit is due—largely not with me. I have largely seen my efforts towards this as being in the engineering, documentation, and guidance departments.

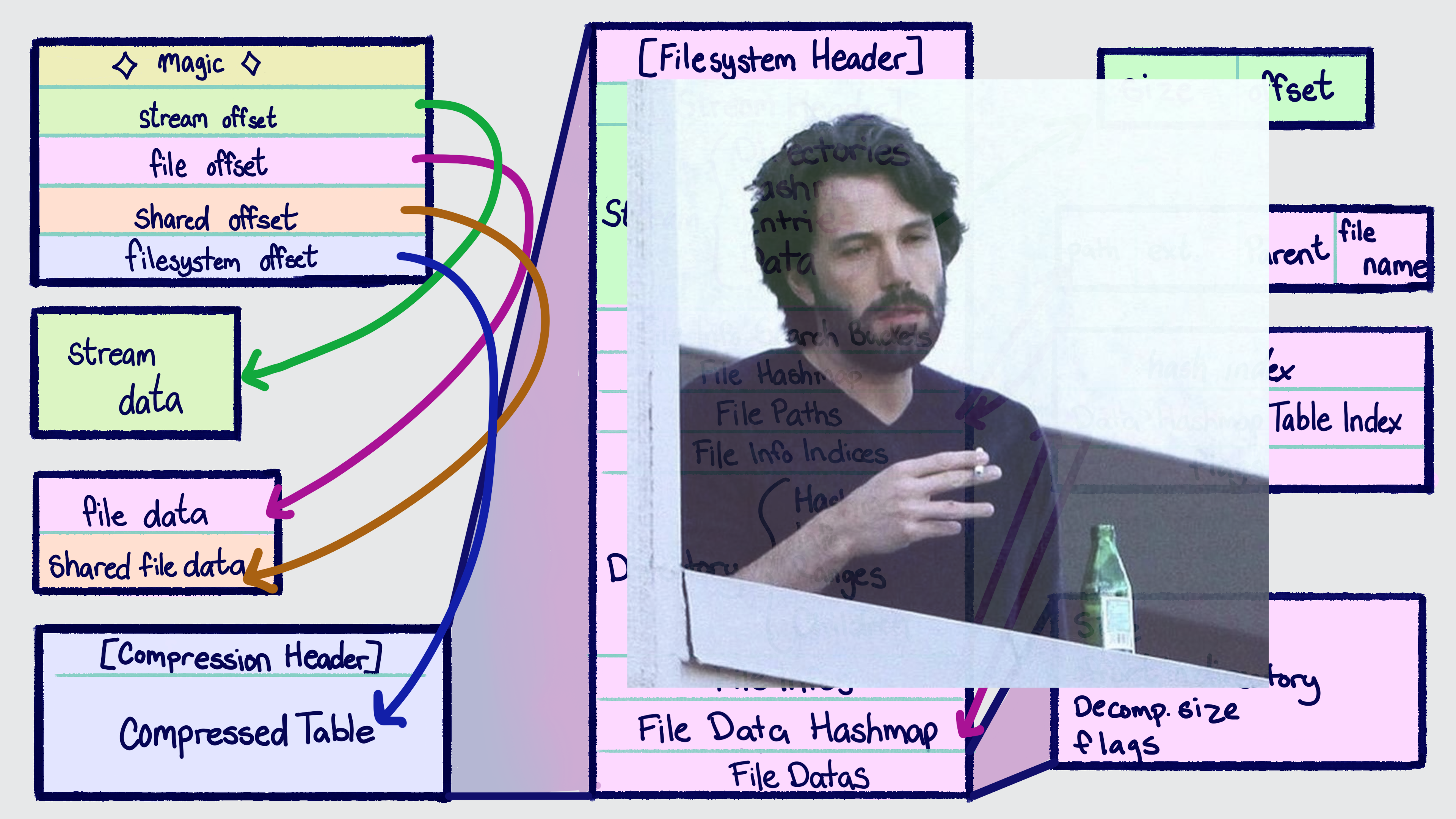

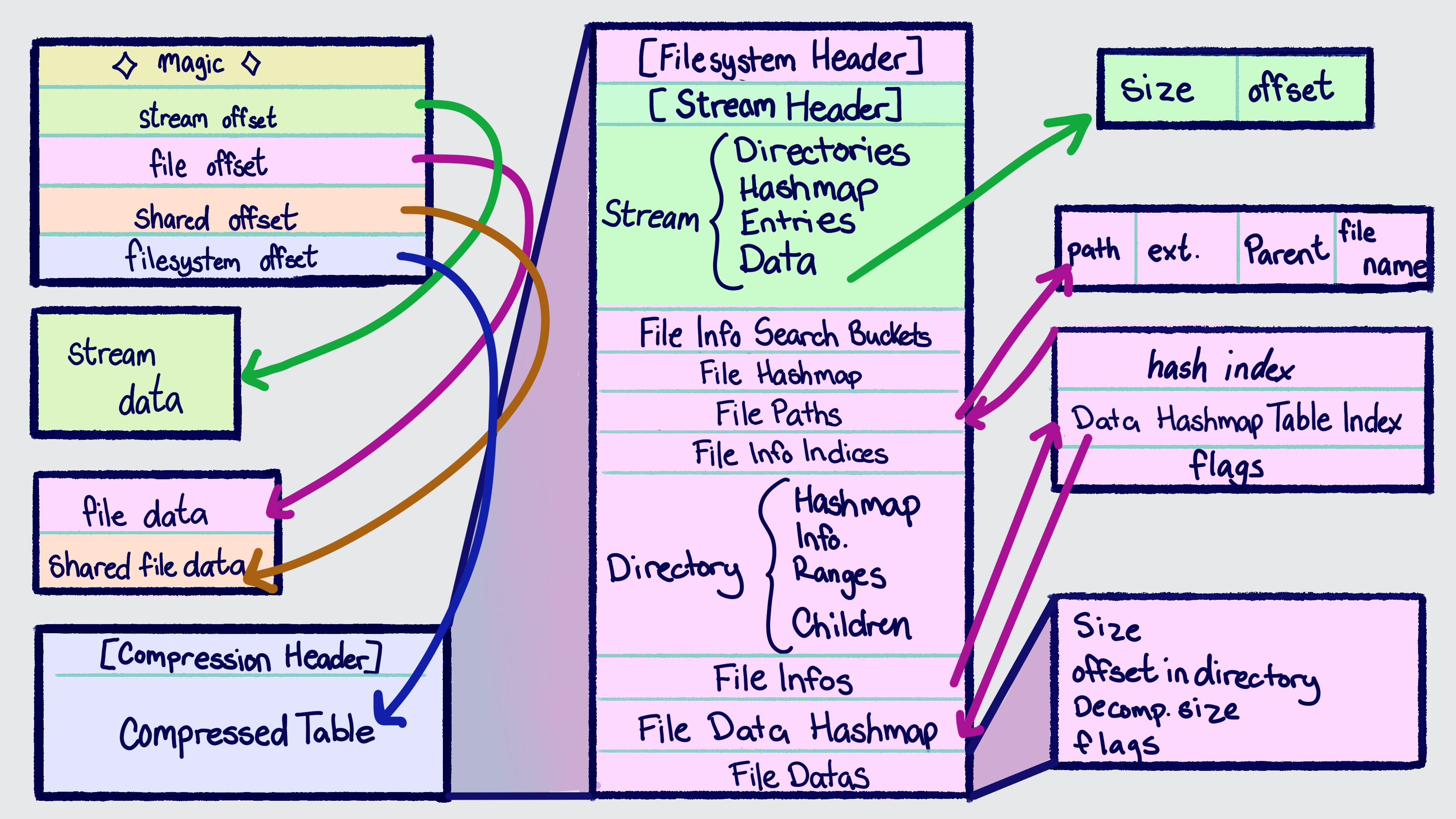

However let's get into the meat of this: the format itself. First, at the top level we have the ARC file:

It's comprised of a header and ~3 sections:

- Stream Data Section - This is immediately after the header (by convention, could be anywhere) and stores all the "stream" (audio, video) files which, due to being dependent on 3rd party code must be uncompressed (the Switch multimedia subsdk only takes a file path and an offset into the file)

- File Data Section - This section contains the contents of basically all the files in the game. Despite a vast majority of the files here being compressed it is by far the largest section.

- There is sort of a subsection, the "shared files", where files which are (again, by convention) sharing a backing data source, have their contents stored. It only really exists in the ARC header, which gives an absolute location of where shared files start

- The "Compressed Table" - The actual filesystem data, all in one big (well, relatively small) Zstandard-compressed block

- The Patch Section - An unused section of the ARC which we only know about from reverse engineering the resource system. Originally this was intended to function similarly to Smash for Wii U and 3ds' "DTLS" system ("dt" being the "data" files, and "ls" being the listing files), which allowed storing patch data in an additional archive which is then merged into the contents of the base game.

If you never look at the compressed table, it's actually a rather simple format! A few offsets in a header that point to a bunch of data. However, this is where things start to get messy.

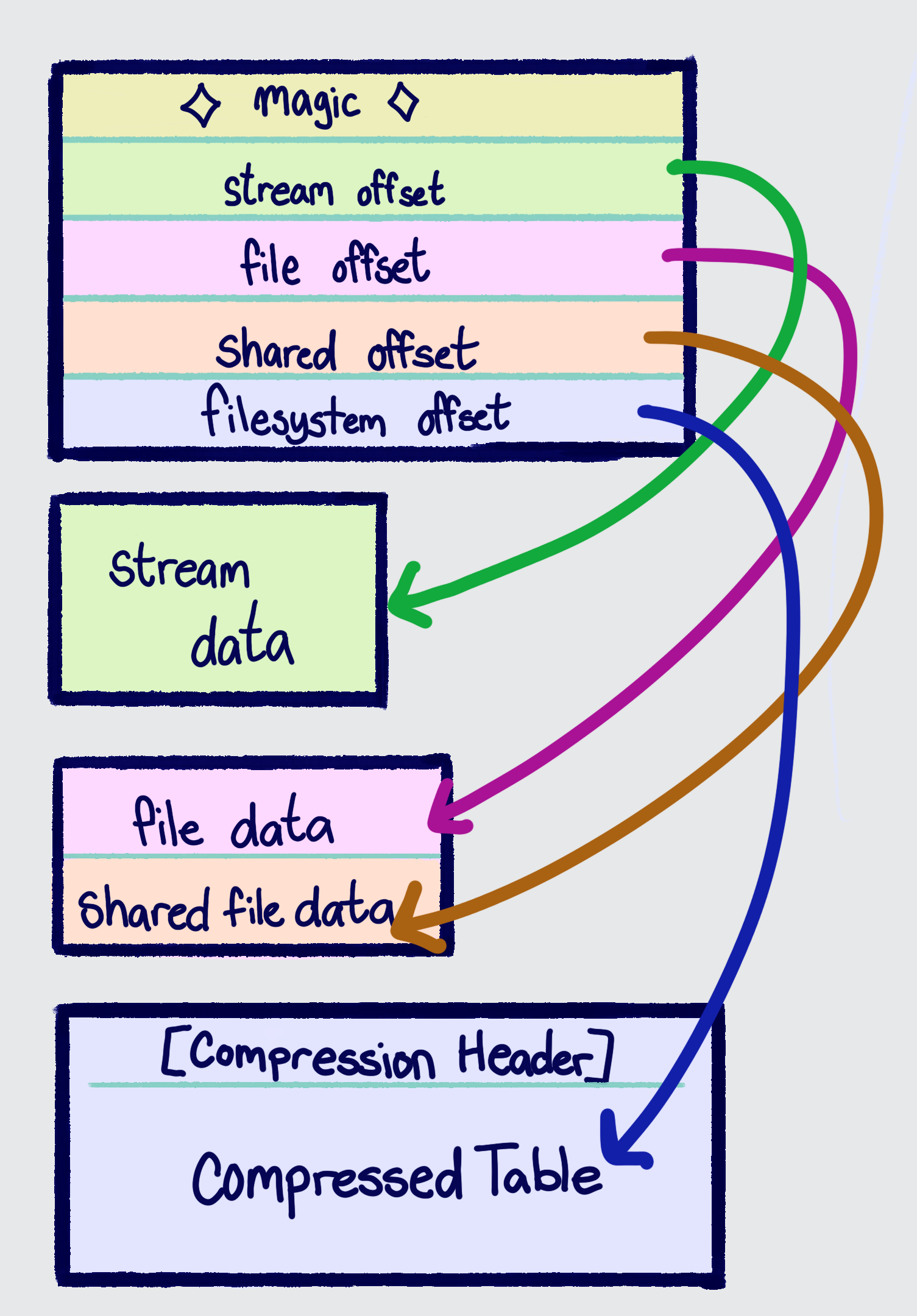

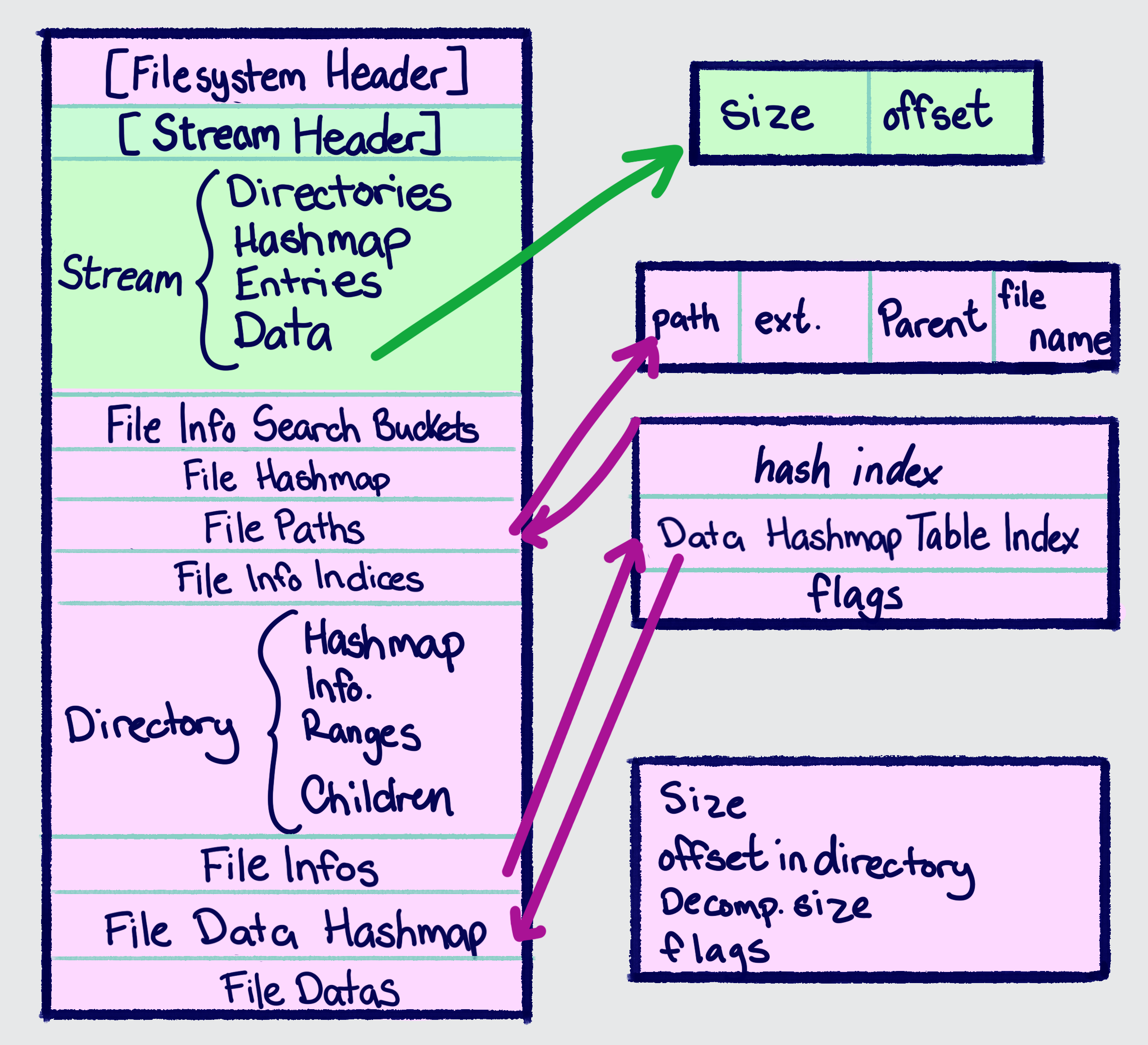

Once decompressed the filesystem looks something like this extremely simplified diagram:

So first off, it should be noted that everything in this part of the format is sequential, meaning the only way to know where a piece of data is is by knowing where the data before it ends. This means that in order to do much of anything, you must parse the entire table before you can do anything. Functionally, this comes in the form of the entire filesystem table being just a bunch of counts followed by an array of structures of that count. So when you see "stream directories" above, it actually involves a count in the "stream header" followed a bit later by an array of bit packed structs representing the directories:

The index and count are then used to form a range within the stream entries comprised of all the files contained in the directory. The hash (a crc32) and the name_length comprise a "Hash40", which is used as a unique identifier throughout the arc and other parts of the game (for basically all of them, the unhashed string is not present in the game, requiring a massive hash cracking effort by the community).

An overview of the contents of the filesystem table and how it's used:

- Stream-related:

- Stream Data Array - describes ranges within the steam data section in which individual files are located

- Stream Data LUT (Not Pictured) - a lookup table to get the index into the Stream Data Array

- Stream Entries - describes individual files, composed of an absolute path hash, some flags, and an index into the Stream Data LUT to get the stream data

- Stream

- Non-stream:

- File Data Array - describes ranges within the file data section and shared data section (the offsets are relative to the start of the file data section for both) as well as whether or not the file is compressed (in older versions of the format, these also described the type of compression)

- File Data Hashmap - a map of file path hashes to indexes into the file info array

- File Path Array - an array of paths to a file. A path is composed of 4 hashes: the full path, the extension, the parent directory, and the file name within the directory

- File Info Array - the core representation of a file. It contains an index into the file path array and an index into the file data hashmap, as well as flags related to the file (is it localized, does it redirect to another file, etc.)

- File Hashmap - a map of the file path hash to an index into the file path array

- File Info Search Buckets - binary search buckets for the file hashmap

Why the Archive Format is so Complicated

This might seem overcomplicated but let's think about some of the goals/constraints of this system:

- The game will always be stored on flash memory

You might be asking: well why would the storage medium affect the file format? The reasoning for that is actually rather simple. If you have either a hard drive or a disk drive, reading a file from disk involves moving the head to the right part of the disk and then pulling the data from that portion of the disk. Now compare that to (a simplification of) flash memory: you request a read at an arbitrary location over the address bus, then a specific flash chip is selected from the chip-select portion of the address, then it uses the rest of the address to select what data within the chip to return over the data bus.

Now let's put that in the context of how it affects our file format: with a game that might be stored on disk, we have to consider the fact that seeks have a cost to them: physically moving the head of the hard drive. This means sequential reads are significantly cheaper, so you want to avoid jumping around to different parts of the file when possible. This can be mitigated to an extent by effective caching either in hardware or by the filesystem driver, however the effects will still be noticable. This means if quick load times are more important than disk space, you might want to store multiple copies of the same data, as you can then store those copies beside other data that will be needed around the same time.

How this effects Smash becomes pretty clear when you look at character skins: each character has 8, and for a majority of skins they are just simple recolors, meaning models/boneset/rigging/normal maps/etc. will likely be identical between skins. So not having to consider a hard drive or disk drive a possibility means that the best option is to save space by de-duplication strategies such as the "shared file" system. If you look at the transition between PS4 Spiderman and PS5 Spiderman, you see the same strategies present, for the same reasons: both the Switch and the PS5 are the first console generation for both game series in which the only storage medium is flash. In the case of Spiderman, as noted by its technical director, it has the paradoxical effect of a larger and more detailed game taking up less disk space.

- The game has a lot of files, but most files are either always loaded together or directly looked up by absolute path (or something similar, like a folder + filename pair, which is effectively an absolute path)

This leads to a bit of a tricky situation where, without optimization, you'll spend a significant amount of time just searching for the file before you can even load its contents. To get around this Smash Ultimate uses the file info search buckets in order to quickly speed things up. What it does is split up all the items in the file info hashmap into sorted sublists called "buckets". You can quickly figure out which bucket a give hash is in by using the "file info search buckets", which is a lookup table that gives you a bucket to search in. A bucket is composed of a start index and a length and describes a range within the file info hashmap to search. Since the buckets themselves are sorted by hash, you can binary search the hashes until you find the hash you're looking for. Also, since a given hash's bucket is determined by hash % N, where N is the number of buckets and % is the division remainder operator, the individual buckets are less dense than if you were binary searching the full set of hashes, further improving lookup times.

As for groups of files, the game improves the load times of these by having a system in which grouped files which aren't shared are placed have their data contents back-to-back to remove the need to decompress them individually, instead using the fact zstandard compressed blocks can be concatenated in order to allow decompressing the entire set of blocks at once. This is also why there is a level of indirection between file paths and file infos. Since "directories" (more aptly named "file groups", despite having directory-like path representations) need to be able to reference ranges of files, the ordering of the level of indirection can be controlled (as it doesn't need to be sorted by hash or be shared like file datas) to allow describing ranges of files.

- The game's resource system is designed around reference counting

Smash, like most large games, uses "reference counting", a technique of keeping track of how many spots in the program are currently using a piece of data. So if two skins load the same model, the one loaded first loads it, then the second one just recieves an identical reference to the already-loaded data. And to know when to free the memory they keep track of how many times it's referenced, incremementing it when a reference is requested and decrementing it when it is no longer being held onto. So in the example the ref count would go 0 -> 1 -> 2 -> 1 -> 0 and then it would be freed until it is next requested.

This might not be obvious at first glance, but due to precomputing all these various lookup tables and hashmaps, it makes it easier to handle this, as the biggest basis of reference counting in this manner is having a unique identifier to request files by. Since for everyone requesting the file both the file's hash and the index of the file in any given table will be identical, so the game just has to store 2 levels of "load tables" to keep track of the reference counts, with the index into these tables corresponding to the indices into the tables within the filesystem table.

Rethinking Arc Handling

Back when I wrote arc-fuse, I noticed that both in C# code and in Rust code, I was finding the parsing unnecessarily verbose. Sequential reads are typically the most common in parsing, so needing boilerplate for them feels off. With arc-fuse I designed and implemented my own parsing system during a particularly long train ride: the core idea was "why can't offsets in files be treated as smart pointers". Because, if you memory map a file, isn't an offset effectively a pointer of sorts? And if you make the memory representation of all your structures be identical to the file representation, the memory-mapping "just works" if you can make the offsets be treated as pointers.

However this creates a few conflicting constraints:

- The in-memory representation of a file offset smart pointer (furthermore a "file pointer") must only contain the offset itself

- The memory-mapped file has a limited lifetime and thus should be a local variable

- In Rust, smart pointers work by implementing the

Dereftrait, which contains no state other than the pointer itself

Unfortunately the only real resolution of this is global state, which... is limiting and gross. This means this parsing system isn't generalizable, not that you'd want it to be due to the fact it isn't possible to multithread parsing, which would be a desirable trait for anything that isn't a 16 GB file like the arc. However I didn't quite give up hope on such a system just yet, despite using it for arc-fuse's parsing.

Eventually this system evolved into binread, which maintains and improves the ergonomics of this system while moving it over to a system of traits, derive macros, and attributes. This also fit the compressed table parsing perfectly as it allows for declaratively specifying earlier variables as the size for an array, as well as being sequential-by-default. It still contains file pointers of sort, however rather than parsing on Deref, it uses a 2-pass parsing system (sequential reads, then seeks), effectively breadth-first parsing. So rather than being a true smart pointer, it's a wrapper type FilePtr<T> which indicates "in the first pass parse an offset, in the second pass jump to it and parse a type T".

One other consideration I took into account was a growing need to work with the in-memory representation of the compressed tables, as tools like Arcropolis need to be able to parse them at runtime, which is a poor fit for using ArcCross (the library, not the GUI, to save you a scroll up) as it's both written in a language hard to use on-console (C#) as well as also being... not great. It's extremely impressive for the short time it was written, but there's a reason why Ploaj chose to put "quick and dirty" in the Github description: it was made very early on and very quickly, as attempting to have a modding scene for an unreleased 1st party AAA game is all the rage these days.

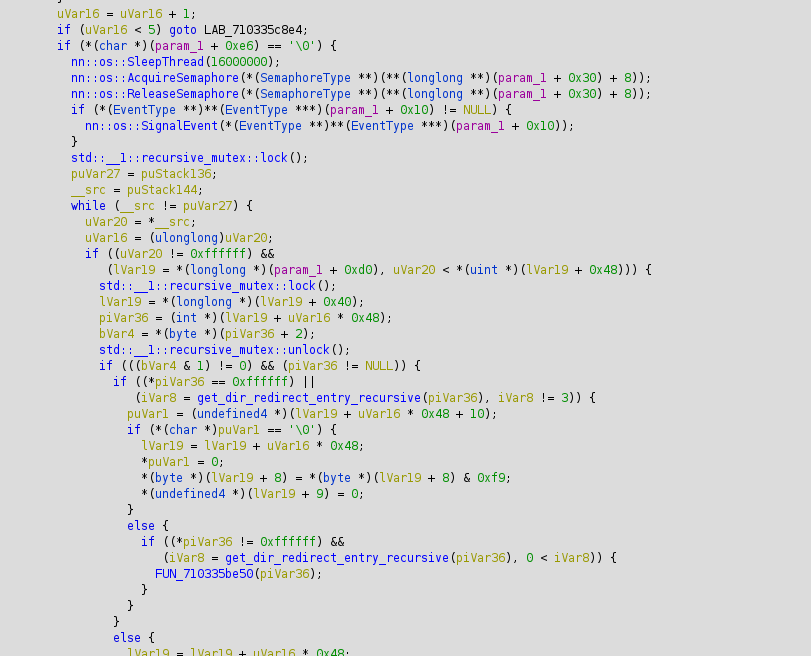

Trying to work with the in-memory representation is an awful experience. It's unsafe (you mess up? the game is now crashed, have fun debugging the segfault without a debugger), it's complicated keeping track of all the lookup tables and hashmaps needed to do even a simple file lookup, and digging through decompilation of the resource loading thread to find out why it's crashing is not a fun time.

Oh I'm sorry, did you want to know why your mod crashed? I thought you wanted to read a multi-threaded thousand line psuedo-C function full of virtual methods, pointers nested 10 levels deep, 20 inlined hashing crc32 implementations because we tried to optimize without knowing what an instruction cache or a "benchmark" is, and some undocumented proprietary SDK functions. Do you like this?? Is this fun for you? Is this how you wanted to spend the next 30 sleepless hours toiling away while a bunch of gaming aficionados tell you to "just fix it"? No? I don't remember asking.

So,

Maybe we need a new approach.

What if there was a way we could significantly reduce the surface of the code that is console-specific to avoid having to debug any lookup logic on-console? Ok yes. There's a way, it might be pretty obvious to those who are familiar with Rust/Programming but: it's traits. The answer is always traits.

So let's throw together a trait real quick:

That was easy! Ok now what does that actually mean.

Since the only real difference between doing these lookups on-console and on a PC is whether we parse it vs the game parses it into memory. So, if we abstract out all the data the game provides, we can just make our own parser, provide the needed data, then do all our lookup testing on a computer that actually has a debugger available to us and which we control more than a fraction of a percent of the running code.

And, as a bonus, this means we get a unified library (smash-arc) for working with this format both on-console and off-console, meaning any effort into improving the performance, API, etc. will benefit basically any use case.

Bringing it All Together

You know how CrossArc is self described as "quick and dirty"? Well, as a linux user (btw i use arch^H^H^H^H ubuntu) I can't say I've ever been much of a fan of CrossArc, as it's Windows-only and runs terribly under Wine. So replacing it has always been on the back of my mind. Observant readers might've noticed that smash-arc is written in Rust, a language infamous for not having great GUI support. Well while it might not have that, it does have unmatched C FFI support. So I worked with ScanMountGoat on making a C interface for smash-arc as well as a .NET core GUI written in C# using Avalonia, making it a cross-platform as well as effectively being a much-needed rewrite of CrossArc.

While I could talk about how much faster it is, how much better I think it is from a technical perspective, whatever. I don't think that's a fair comparison, nor does it reflect what users care about. CrossArc was extremely well put together for being made in only a few short weeks, is performant enough for what people want, and is extremely featureful, and most modders play games (and thus, for the most part, use Windows) so cross-platform isn't something that matters for most. So what does a replacement really even give us?

Well, the thing about smash-arc is it really doesn't care about where the data comes from, the parser is generic over basically any data source. And while the data.arc is 16 GB big, the compressed file table is in the lower order of tens of megabytes. So if we can read just the compressed table, we already can load everything but the actual contents of the files, allowing opening an arc over the network. Which, for those who aren't familiar with smash modding, is a bigger deal than it seems! Dumping a 16 GB file to your SD card then transferring it over to a PC takes a lot of time, and as you might remember from the beginning of the post Smash has gotten a lot of updates, some barely changing anything (still requires a full redump of the game to continue modding though!).

Anyways without further ado, ScanMountGoat and I present ArcExplorer, a GUI for browsing and extracting files from Smash Ultimate's archive format, from a local file or over the network: