Reverse Engineering MSC Bytecode — File structure

While not all scripting languages in fighting games are the same, the process can be applied to just about any filetype in general. First thing I do when I open up a filetype is lay out some guesses about structure. For this, any old hex editor will do. It helps to have things such as the ability to highlight a section of bytes and see what the equivalent values are for standard types (int/float/etc). It it worth noting that a basic understand of hex, how ints are represented in hex, what “endianess” means and what ascii is are assumed by this. If you are unfamiliar with any of the aforementioned topics it is advised you google and read up a bit before going through.

Header

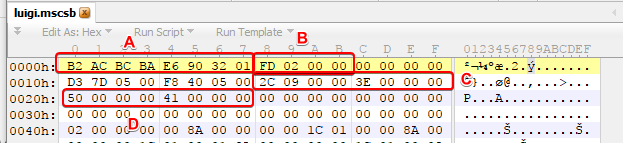

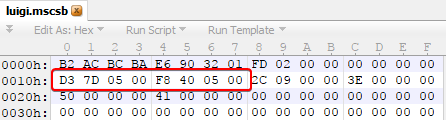

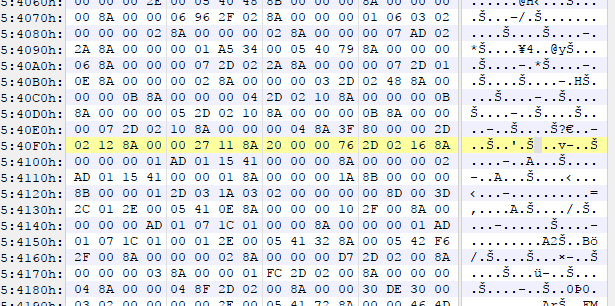

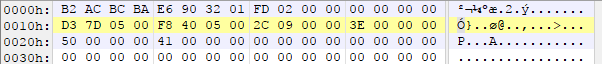

The first things I notice are (A) it starts with some semi-random looking bytes. My initial thoughts are that it is either a hash (because it’s semi random) or that it’s the magic (because it’s at the very beginning). By looking at another couple files I can quite easily verify it’s not a hash (because the file contents are different but they are the same) so I can safely assume it is a magic string just to indicate that this is an MSC file and not some random file. Next up (B) has two zeros trailing so it is looks a lot like a little endian number, which is rather surprising given that the Wii U uses a big endian architecture. Since it is an odd number (0x2FD) and therefor not 4 byte aligned (which is rather standard), I can somewhat safely assume it is not an offset, especially when we look at 0x2FD and find there isn’t much there. I did not figure this out my first time but it turns out the entire first 0x10 bytes is a part of the magic and is the same in every single file, go figure. Could mean something, but doesn’t really matter considering it is the same in every file.

At this point there is no way to be sure exactly what it is, but given the file is decently large (as far as some of these files go) it isn’t out of the question that it’s a count of some sort, an offset to a part of the file other than the beginning, etc. However we’ll revisit this later. For **(C and D) **we have two more 32 bit integers each, again signified by the trailing zeros and the fact we’ve assumed it is little endian. After (D) we have a large amount of zeroes, which we can likely assume are there to pad out the rest of the header, also indicating the end of it.

Header Offsets

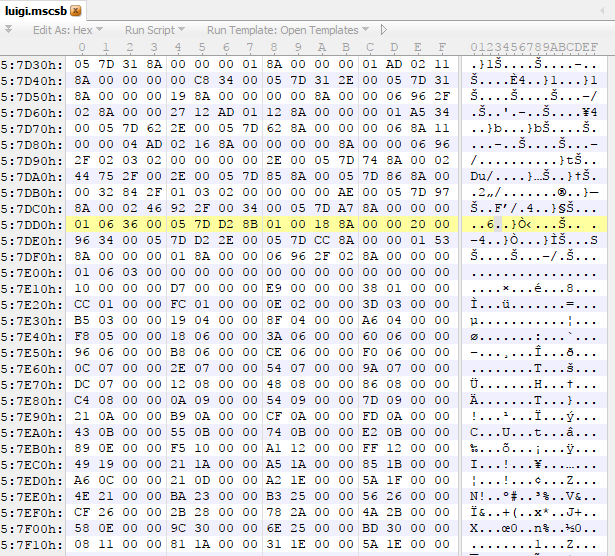

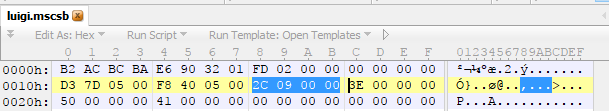

Circling back to the 8 bytes from earlier, we can see that each set of 4 bytes has a trailing zero it lead me to believe that we have more numbers. Given the size of them, we can see they most likely going to be sizes or offsets. If we jump to 540F8 (The second of the two numbers) we land right in the middle of the script data (we know this is script data just from the filesystem which labels it as such, with our file being from:

/data/fighter/luigi/script/msc/luigi.mscsb

The way you can more or less tell apart the script data and the rest of the file format is the amount of noise. Here at 540F8 there is a lot of noise as well as a lot of repeating bytes (which most likely represents a command repeated often). Here we see the byte 8A followed by 00s a lot.

In contrast we have position 57DD3, the first of the two offsets we saw in the header.

Script Table

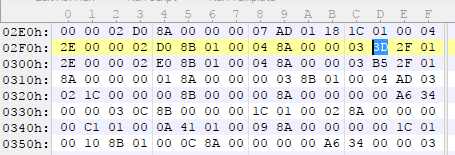

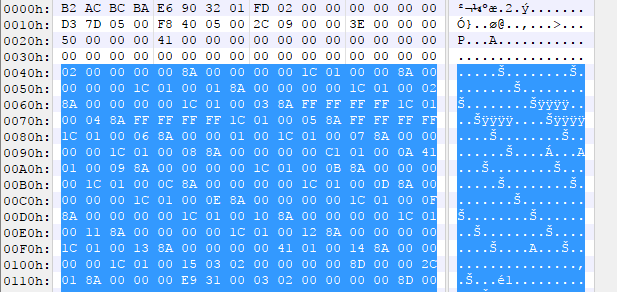

Not long after 57DD3 we have a section with very uniform columns of data.

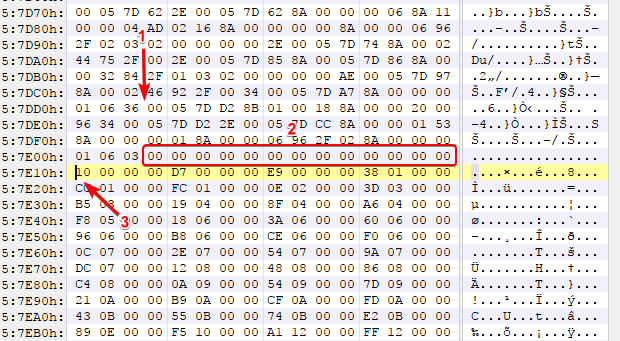

Now we have these uniform columns, if we look at them we see a lot of 4 byte aligned sections with 2–3 leading zeroes, which you might remember indicates a little endian integer is there. So we have a table of numbers here, but you should remember there has to be some way for the program (in this case the game) to be able to get to this table. Logically, since there likely will not be an inline table in a script, we can assume this is separate from the script section and the only thing in the header near this table is the offset we just found (in this case D7DD3). So how I would handle this is I would have a hunch that the file offset (in this case D7DD3) is relative to something other than the beginning of the file. So how do we figure out what this offset is in order to use this in our own programs (which is likely the end goal of reverse engineering the filetype)? First up lets make a guess at where the table starts.

I guessed that (3) was the start of the table due to the fact that (2) has a bunch of zeroes that are likely just padding out the scripts to get to the table (often times files are 0 padded in order to stay 4 byte alligned when writing ints/floats/whatever). So our distance from our offset from the header (1) to the start of the table (3) is 0x3D. However 0x3D is odd, which is an awkward amount for a offset to be relative to. But you may notice, it’s a round 0x30 to get from **(1) **to our padding. If we put 2 and 2 together we can then guess that the table is located from the offset + 0x30 + however much to pad it to be 0x10 alligned (The next line in a hex editor). In order to verify this we can see if this holds up in other files of the same type (It does). So let’s take a look at the table itself now that we can consistently get to it.

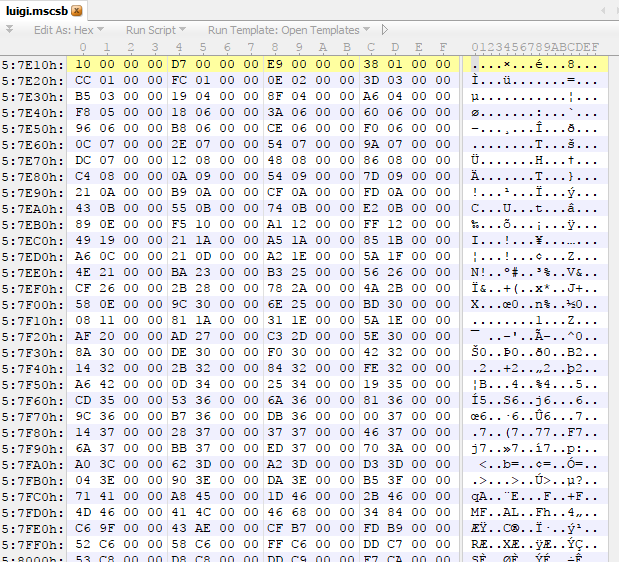

We have values from 0x10 to 0x57D86, ascending in value in somewhat small steps. We can find that all of these land in or near the script area we mapped out earlier, however the first value (0x10) is not in the script data, it’s in the header.

But considering know that all the other ones are valid script offsets, I’d say it’s quite unlikely that they aren’t all offsets into script data. This is when that handy offset of 0x30 comes in handy, if we add 0x30 to 0x10 we get 0x40, which lands us right at the start of the script data.

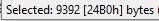

If this seems like yet another leap in logic, remember you can also think of it the opposite way in that the script starts at 0x40, the first offset is 0x10, the difference is 0x30 which happens to match up to the starting point for an offset from earlier. And if your issue is “why is it offset by 0x30”, the answer is that the offset isn’t about how far into the file, it’s about how far from the header is it. It’s just based on how the programmers of the game wrote the code for reading and writing this file. Now that we know why the table is used, let’s find a more consistent way to find the size of it. Usually in programming a table like this is stored in an array. When you work with the array you generally don’t work with the size, you work with the size of individual parts of the array (in this case an array of integers would have a size of 4 for each integer) and the number of items in the array. So most likely we’re looking for a count. The way I usually do this is highlight all the bytes in the table, see how many bytes my hex editor says I’ve highlighted, then divide that by the size of each item.

Since we have 0x24B0 bytes and each int takes up 4 bytes, that means 0x92C. If we can’t find this anywhere we should look for something that evenly divides this, because in some cases an entry in the table might have more than one int. In this case though, it’s just one int per entry in the table. If we look back at our header though we’ll find that one of our unknown ints was exactly 0x92C so in this case it just worked out with just the number of ints in the table.

Now we have a table that splits up our script data into smaller chunks (scripts) and we know how to read it (how to locate it, how big it is, what it contains).

String Section

So lastly we have the string section at the end. It comes after the script table and is pretty obvious how it is laid out.

This is part of why it was so easy to find the end of the table, because we immediately see strings. There are, however, no offsets to this string table. Which means we have to assume that it just comes right after the script table (in some other files it doesn’t line up so cleanly so you have to deal with yet another section of padding). This part was rather simple so I’ll be brief. Each string has padding after it, this padding always brings the string to the same length. So all we have to do is find out how many strings there are and how big they are. There are 0x41 strings and in our header we have the little endian int 0x41. The size was always (in this file) padded out to 0x50 bytes. There also happens to be a 0x50 in the header, if we check other files (most of them have the same padding size which was a bit annoying) we find that they also follow this rule. And that covers the entire file format. You might notice there is still an unknown int in the header, I don’t know what it is and changing it doesn’t seem to change anything, it just has a different value for articles (projectiles) vs characters. Sometimes there just isn’t a point in reversing a certain part because it doesn’t matter.

See part 2: Reverse Engineering MSC Bytecode — Script Data